Research

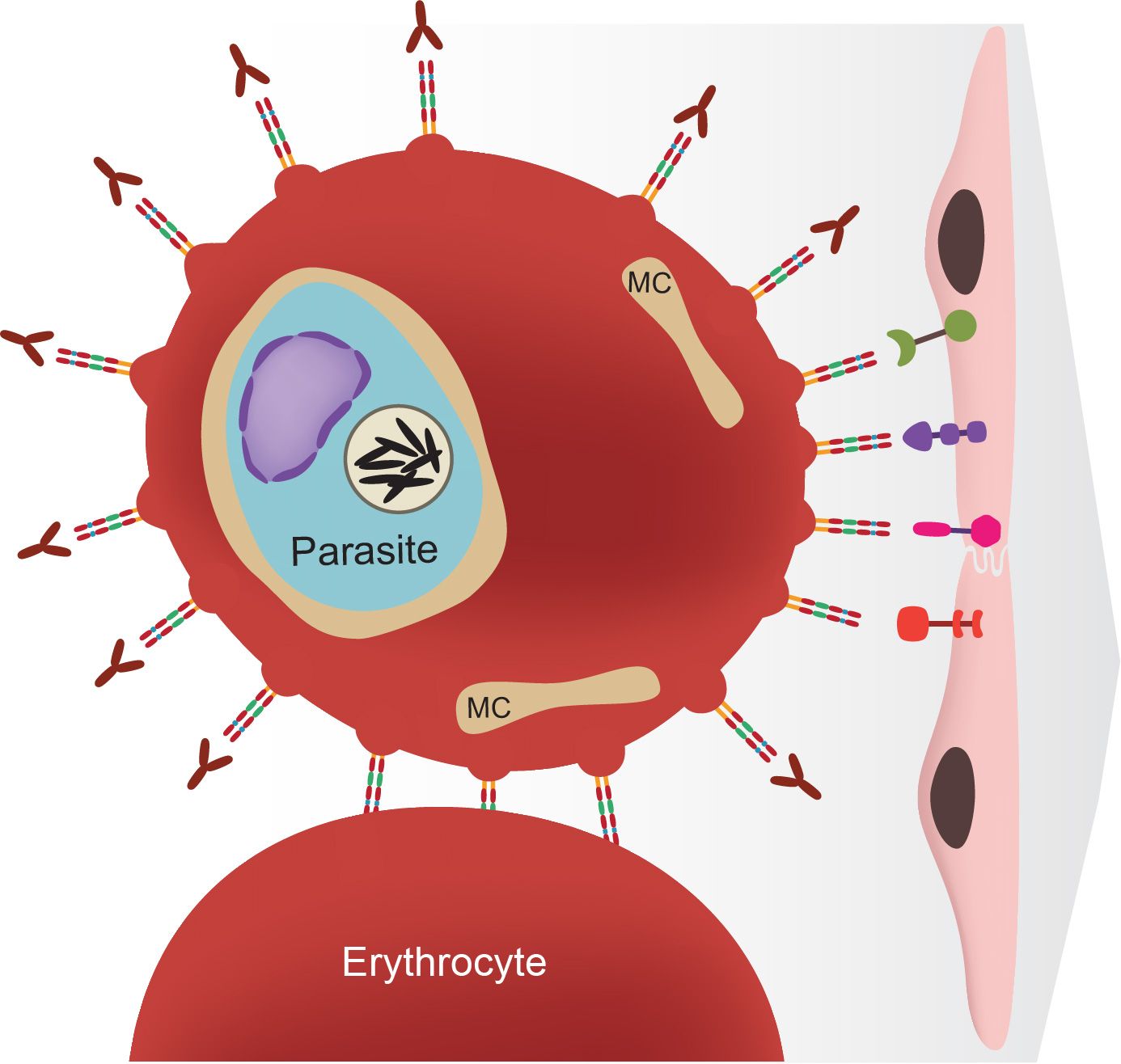

Malaria remains one of the most important infectious diseases in the world today, infecting 300-500 million people yearly and resulting in up to a 600,000 deaths, primarily of young African children. The most severe form of this disease is caused by infection with the mosquito borne protozoan parasite Plasmodium falciparum. This parasite lives by invading and multiplying within the red blood cells of its host, causing disease through anemia resulting from red cell destruction, and also through modifications that are made to the surface of infected red cells. These modifications make infected cells cytoadherent or "sticky", allowing them to adhere to the walls of blood vessels, leading to obstruction of blood flow and such clinical manifestations as the often-fatal syndrome of cerebral malaria. In addition, parasites are capable of undergoing antigenic variation, a process of continually changing the identity of proteins on the surface of infected cells, thus changing their antigenic appearance and avoiding the immune response. In this way the parasite "hides" from the immune system, promoting a long term, persistent infection that is difficult to clear.

Figure 1 Drawing of a malaria parasite living inside a human erythrocyte (or red blood cell). The parasite places proteins on the infected cell surface, leading to adhesion to the endothelial cells of the blood vessel walls or to uninfected erythrocytes. From Deitsch and Dzikowski, Annual Review of Microbiology, 2017.

Both the cytoadherence of infected cells and the process of antigenic variation are controlled by a family of genes called var. Each parasite possesses up to 60 different var genes within its genome, maintaining most of the genes in a silent state, while expressing only a single gene at a time. Each var gene encodes a protein that is placed on the surface of the infected cell, making the cells cytoadherent. When an infected person mounts an immune response against the protein encoded by the expressed var gene, the parasite switches to expressing a different copy. This changes the immunological appearance of the infected cells and allows the parasites to avoid destruction and maintain the infection. The focus of the research project being conducted the Deitsch lab is determining the molecular mechanisms that enable parasites to precisely regulate expression of the var gene family. The ability to express only a single gene at a time, and to switch between different genes to avoid destruction by the immune system is key to the parasite's ability to maintain an infection and cause disease. It is hoped that gaining a better understanding of this process will lead to more effective treatments and disease intervention strategoes for the millions of people at risk in the developing world.

Current Projects:

- Transcriptional regulation of the var gene family.

- DNA recombination and genome diversification of malaria parasites.

- How malaria parasite sense and respond to environmental changes.

- Metabolic adaptions by parasites to different anatomical niches.

Bio

Deitsch received his BS from Central Michigan University in 1989 and his PhD from Michigan State University in 1994 under the mentorship of Professor Alexander Raikhel. He then worked as a postdoctoral fellow at the National Institutes of Health from 1995-2001 in the laboratory of Dr. Thomas Wellems. Deitsch joined the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at Weill Cornell Medicine in 2001 and the BCMB Program of WCGS in 2002. He currently serves as a co-Chair of the BCMB Program.

Distinctions:

- New Scholar Award in Global Infectious Diseases, Ellison Medical Foundation, 2002.

- Presidential Early Career Award in Science and Engineering (PECASE), 2002.

- Excellence in Teaching Award, Weill Cornell Medical College, 2014.

- Teaching and Mentorship Award, Weill Cornell Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, 2022.

- International Board of Directors, Sanford F. Kuvin Center for the Study of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel, 2022-present.

- International Advisory Board, West African Centre for Cell Biology of Infectious Pathogens (WACCBIP), University of Ghana, 2017 – present.

- Course Director, “Biology of Parasitism”, Marine Biology Laboratory, Woods Hole Massachusetts, 2011-2015.

- Course Director, “Middle East Biology of Parasitism”, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, 2022-present.